Introduction

Although classically described as a relapsing, chronic, pruritic, and inflamed rash on flexural areas of the body, atopic dermatitis (AD) is a heterogeneous disease with a wide range of manifestations. Presentation of AD varies in symptoms, severity, location, and disease course, which is further complicated and modulated by temporal, regional, ethnic, immunopathogenic, microbial, genetic, environmental, and age-related factors.1–13 In 2022, an expert panel of ten leaders in chronic inflammatory dermatoses approved the concept of AD as a spectrum disorder with diverse presentations in which “seemingly distinct dermatologic disorders can present as a manifestation of atopic dermatitis.”14 The heterogeneity of AD has prompted research that seeks to discover specific subcategories of AD in order to enhance treatment specificity, personalization, and patient outcomes. Rooted in pattern recognition, traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) practices present unexplored potential to differentiate AD subtypes.15

Atopic dermatitis from a conventional perspective and the shift towards personalized medicine

AD is a clinical diagnosis dependent on patient history, characteristics of skin lesions, and clinical signs, with no biologic markers that distinguish it from other conditions.2,13,14 The variety in clinical presentation has resulted in diagnosis criteria with a large number of criteria, such as the 1980 Hanifin and Rajka criteria with 4 major and 23 minor criteria.13 Despite the range in disease presentation and symptoms, AD is still treated as a single diagnosis. Unsurprisingly, a “one-size-fits-all” treatment approach to such a heterogeneous condition contributes to differing responses to treatment, likely due to variations in underlying mechanisms of pathogenesis.16–18 With the development of more targeted therapeutics, such as biologics that block a single cytokine, it seems unlikely that these therapies will be efficacious in all AD patients.19 The growth of personalized medicine aims to address the need for individualized approaches in treating AD.

Attempts have been made to classify AD subtypes to increase specificity of treatment and diagnosis. Subtypes have been developed based on extrinsic and intrinsic phenotypes, ethnicity, genetic mutations, age, and temporality (acute vs. chronic).2,20 Additionally, endotyping approaches, which analyze molecular mechanisms, have made distinctions based on “cytokine expression, allergen properties, epidermal barrier conditions, ceramide variation, the involvement of innate immunity, and serum biomarkers.”21 However, the feasibility of implementing endotype subtyping into daily clinical practice is still low. The need for personalized treatment that considers individual pathogenesis in AD is evident. However, biomarkers to conduct personalized treatment are still an evolving area of research, far from implementation into clinical practice.

Traditional Chinese medicine classification and treatment of atopic dermatitis

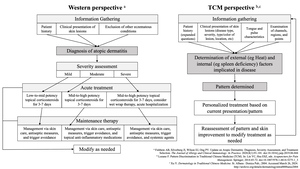

TCM approaches AD as not one condition, but many, using pattern recognition (Figure 1). Xu conveys that the initial visual diagnosis is central to pattern recognition, which considers the presentation of skin lesions, including the location, color, severity, and dryness or dampness.22 Visual diagnosis is not limited to the skin, however, as examination of the tongue is critical to providing additional insight into the disease state.22 Conducting a patient history from a TCM approach takes on a more holistic lens, asking more questions than would be typical in a Western setting. For example, questions about urination and thirst may be asked to elicit information about dampness and heat patterns, while questions about sweating may reveal heart or lung patterns.23 The characteristics of one’s pulse is also assessed, which could be slippery, rapid, soggy, or wiry, for example.22 Lozano describes how acupuncture channels, points along these channels, and the regions of the body associated with these channels are also examined. For example, pain in the frontal forehead, upper teeth, tongue, stomach duct, upper abdomen, and lateral aspect of the legs could be indicative of disruptions to or blocking of the spleen and stomach channels.23 Using all of this information, specific disruptions in Qi (life energy) and Yin and Yang (balance) are distinguished, which make up the TCM pattern observed.24,25 For example, some causes of Qi disruptions include “Wind,” “Coldness,” “Summer-heat,” “Dampness,” “Dryness,” or “Fire evils.”26,27 Once the pattern is determined, specific treatment is selected to address the distinct sources of these disruptions. This highly individualized approach considers the vastly different presentations of AD, treating each pattern in a specific manner. Over time and treatment course, the evolution of the observed pattern and improvements in the skin are observed to continually modify treatment.

The main external factors relevant to the pathogenesis of AD are the accumulation of “Dampness,” “Heat,” and “Wind” in the skin. Understanding which organs (in the context of TCM, not necessarily the anatomical organs) — such as the heart, spleen, and/or kidney — are implicated in disease is essential to treatment, as metabolic dysfunction of these organs contributes to accumulation of the aforementioned pathogenic external factors.22,24,28 For example, dysfunction of the spleen can contribute to dampness, ultimately causing maceration and erosion of the skin.22

TCM medicinal treatments intend to address these specific disruptions, such as “heat-clearing,” “damp-resolving,” and “damp-draining” substances.29 To select a treatment regimen, TCM practitioners recognize patterns that reflect these disruptions. The heat pattern tends to manifest as erythema and swelling that can lead to infection. Dampness presents with lesions that linger without healing, primarily in the lower extremities. Wind can present as intense itch of multiple lesions.22 Pattern identification involves identifying the contributions of each of these factors in the individual’s disease presentation. Xu presents five patterns of atopic eczema: Damp-heat in infants (predominance of dampness), Fetal heat, Damp Heat in children, Spleen and Stomach deficiency, and Blood dryness.22 These patterns are differentiated by patient age, location and characteristics of lesions, intensity/localization/temporality of itching, sleep patterns/disturbances, characteristics of stools and urine, appearance of the tongue, and characteristics of the pulse.22

With different patterns of AD come different modalities of treatment, such as clearing heat and transforming dampness to address damp-heat patterns, or enriching Yin and eliminating dampness to address blood dryness.22 TCM presents a different way to diagnose and address AD, through identifying the pattern exhibited by the patient and using modalities focused on correcting Qi disruptions, which may change visit to visit depending on the current pattern of disease.30 Unlike allopathic approaches that specify treatments for a disease, TCM evaluates the pattern and aligns treatment, such that several patients with the same diagnosis of atopic dermatitis may have vastly different patterns and treatments from a TCM perspective.

Efficacy of traditional Chinese medicine in treating atopic dermatitis

TCM herbs and modalities, like acupuncture, have demonstrated efficacy in treating AD symptoms. Compared to placebo herbs, TCM herbs have contributed to improvements in itching, erythema, surface damage, and sleep.31 Even compared to patients using a combination of oral antihistamines, placebo pills, and topical 1% mometasone furoate, patients using a TCM herbal pill alone and patients using a TCM herbal pill with topical herbal TCM experienced greater decreases in the Scoring Atopic Dermatitis Index (SCORAD) and greater improvements in quality of life measures.32 Additionally, TCM herbs have been shown to decrease topical corticosteroid use.31,33 In a randomized controlled trial, twice-weekly acupuncture was also effective in improving SCORAD scores in AD patients, although more rigorous studies are needed.34,35 A combination of acupuncture and TCM demonstrated improvements in Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI), Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), and subjective perception of itch.35 Systematic reviews have found that TCM herbs are effective in treating AD, although current studies lack rigor in their design.36,37

Existing studies generally demonstrate efficacy of TCM herbs in treating AD. However, the majority of these studies do not use the personalized and pattern-based method of diagnosis and treatment selection that characterizes TCM practice. In 2005, one study of patients using TCM prescribed by a TCM practitioner found that nearly 60% of caregivers thought that the prescribed TCM improved their child’s AD.38 A retrospective analysis of TCM prescriptions for AD in Chang Gung Memorial Hospital in Taiwan found that the most commonly prescribed herbs were Xiao-Feng-San (Eliminate Wind Powder) and Bai-Xian-Pi (Cortex Dictamni) and most herbal treatments were “exterior-releasing” (20.23%) and “heat-clearing” (41.93%).39 More research using validated measures, such as SCORAD, EASI, and DLQI, is needed to understand the efficacy of TCM treatment in the context of personalized and pattern-based diagnosis.

Case 1

Consider a case presented by Xu.22 A 15-year-old female with a past medical history of more than 10 years of generalized exudative itchy pimples presents with red papules densely distributed on her limbs and trunk, with scattered erosions. Erosions are worst on the legs and hinder mobility. Discharge of exudate, blood, and pus is also present, with resultant yellow crusting. Scratch marks are present around the lesions, accompanied by redness/erythema. Her pulse is deep and wiry. Upon oral examination, the body of the tongue was pale with a thin white coating.

From a Western perspective, this would be considered severe AD with heavy involvement of flexural areas. The oozing and bleeding with yellow crusting would suggest secondary infection, while the “pimples” may suggest bacterial folliculitis. A skin culture may be done, and would likely result in abundant Staphylococcus aureus, for which an oral antibiotic, such as cephalexin, would be prescribed. Topically, a mid-potency corticosteroid such as triamcinolone could be used twice daily along with liberal moisturizer. This can possibly be paired with wet-wrap therapy (ie a damp garment over the area) at night for at least a few days to quickly reduce the flare. Once the condition has improved, the patient could be shifted to a non-steroidal regimen, such as tacrolimus ointment and moisturizer in trouble areas. Triamcinolone could be used again in the event of a flare. If this regimen was insufficient to establish or maintain good control, this patient would be a candidate for a systemic agent such as a biologic or phototherapy.

From a TCM perspective, Xu described that the treatment goal would be to eliminate pathogenic factors and harmonize Qi and Blood by dispelling Dampness, Wind, and Toxicity, and support Vital Qi (Zheng Qi).22 This would be achieved by a twice daily herbal decoction along with external application of Xi Shi Xin Ba Gao (Dilute Plaster Preparation). In follow up appointments, treatment would be modified based on the progression or improvement observed. For example, consider a situation where, after 12 days, most of the lesions subsided and pruritus declined, but the patient still had papules on the lower extremities. The treatment would then be changed to a different herbal combination and external application of Tuo Se Ba Gao Gun (Decolorizing Medicated Plaster Stick).22

Case 2

Consider another case presented by Chang and González-Stuart.40 A 17-year-old male presents with multiple pale red lesions on the upper and lower extremities, with lichenification concentrated at the elbows, ankles, wrists, and knees. Xerosis, hyperpigmentation, and scratch marks are evident. Edema and erythema are present in the facial area. Pruritus was constant, non-radiating, and present on the upper and lower extremities, but was most severe on the face. Weekly, the pruritus of the extremities alternated between the upper and lower extremities. The pruritus worsened during winter and the end of the day. The patient tried topical pimecrolimus cream, with no improvement. The patient’s father has a history of allergies. The patient also has a past medical history of allergy to sugar. His pulse is rapid and slippery. Upon oral examination, the body of the tongue was pale and swollen with a thin, watery, white coating. Red prickles were present on the upper half of the tongue. The tip of the tongue was red.

From a Western perspective, this would likely be considered moderate atopic dermatitis. Although a more xerotic and lichenified presentation than the open, oozing presentation of the prior patient, the treatment approach would be very similar, differing only in the skin culture and consideration of an antibiotic. A mid-potency topical steroid and liberal moisturizer, potentially paired with a wet-wrap, would be used to reduce the flare. A non-steroidal regimen could be considered upon improvement and corticosteroids could be used in a flare. Inability to maintain good control with this regimen would lead to consideration of a systemic agent.

From a TCM perspective, the diagnosis was Dampness with Spleen Deficiency and Heart Shen dysfunction. This was treated with acupuncture treatment and Chinese herbal medication. Once weekly acupuncture focused on acupoints along the Spleen and Heart meridians that tonify the Spleen, reduce Dampness and inflammation, and improve mood. The Chinese herbal medicine consisted of an encapsulated pill of herbal powder combinations of 3 capsules taken 3 times a day.40

Future Directions

As demonstrated in the cases, situations that may be treated similarly with a Western approach are addressed differently from a TCM approach. Pattern-based diagnosis, used in TCM, presents a modality to further characterize AD subtypes. Unlike biomarker analyses, TCM diagnosis is based on disease presentation and is already practiced, making it more feasible to implement into clinical practice. Before doing so, rigorous studies should be conducted comparing the efficacy of TCM pattern diagnosis and treatment to Western standard of care diagnosis and treatment (Figure 1).23,41 Learning from TCM practices, which already treats AD as many different conditions, presents an opportunity to distinguish subtypes of AD, personalize treatment, and improve patient outcomes. To achieve this goal, TCM principles may be adapted for a Western context. Lozano proposes a step-by-step method of integrating TCM and Western diagnosis and treatment processes (Table 1).23 Leveraging a TCM diagnostic approach with Western medicine may be an avenue to advance personalized treatment in atopic dermatitis.

Disclosures

Dr. Lio reports research grants/funding from AbbVie, AOBiome; is on the speaker’s bureau for AbbVie, Arcutis, Eli Lilly, Galderma, Hyphens Pharma, Incyte, La Roche-Posay/L’Oréal, MyOR Diagnostics, ParentMD, Pfizer, Pierre-Fabre Dermatologie, Regeneron/Sanofi Genzyme, Verrica; reports consulting/advisory boards for Alphyn, AbbVie, Almirall, Amyris, Arcutis, ASLAN, Boston Skin Science, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Burt’s Bees, Castle Biosciences, Codex Labs, Concerto Biosci, Dermavant, Eli Lilly, Galderma, Janssen, Johnson & Johnson, Kimberly-Clark, LEO Pharma, Lipidor, L’Oréal, Merck, Micreos, MyOR Diagnostics, Regeneron/Sanofi Genzyme, Skinfix, Theraplex, UCB, Unilever, Verrica Yobee Care; stock options with Codex, Concerto Biosciences, and Yobee Care. In addition, Dr. Lio has a patent pending for a Theraplex product with royalties paid and is a Board member and Scientific Advisory Committee Member of the National Eczema Association.

Courtney Chau has no conflicts of interest or relationships to disclose.

Funding

This research received no funding.