Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is an extremely prevalent disease that affects up to 20% of children and 10% of adults in developed countries.1 The prevalence has been increasing worldwide, especially in urban areas.1,2 AD is primarily considered an inflammatory disorder that arises from a myriad of factors, both genetic and environmental. Understanding risk factors, underlying mechanisms, and treatment strategies is essential for promoting health and improving outcomes.

The clinical presentation of atopic dermatitis varies depending on the underlying causes and severity of the condition. Pruritus is a principal symptom of AD and significantly impacts the quality of life of patients with the disease.1,3 Severe pruritus disturbs sleep, occupational and educational performance, and is linked to anxiety and depression.1 The symptom of itch clearly indicates a neuronal contribution to the disease, and while the focus of research and treatments on itch is experiencing a renaissance in publications, there is still a scarcity of information on the neuronal aspect of the disease, especially in clinical literature.

This narrative review provides an overview of the most recent articles researching alterations of peripheral and central nervous systems associated with and caused by atopic dermatitis and the treatments to alleviate these symptoms.

Methods

This review was conducted through a search of primary literature and review articles on PubMed and Google Scholar. The major search terms used were for itch pathways in atopic dermatitis, neuronal changes in AD, central sensitization, peripheral sensitization, acute vs chronic changes in AD, and for morphologic changes in AD. Related search suggestions from Google Scholar and PubMed were also investigated.

Results: Literature Review

Itch Pathway

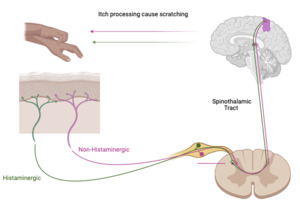

Itch is a defining symptom of AD. Itch has two dominant neuronal pathways: chronic (non-histaminergic) which is dominant in AD and acute itch (histaminergic). Itch starts with the peripheral nervous system (PNS) in the skin. The skin is innervated by autonomic and primary cutaneous sensory nerves (afferent nerves). These afferent nerves have cell bodies in the dorsal root ganglion and axons that terminate in the dermis or epidermis. Numerous neuropeptides and neurotransmitters are released from these axons that can interact with Langerhans cells (a type of dendritic cell) and keratinocytes. After activation of these cutaneous nerves, the signal is transmitted through the spine, via the spinothalamic tract (STT), to the thalamus and then to various regions of the brain.3 Both non-histaminergic and histaminergic itch utilize this pathway but have distinct neurons that are specific to them in the periphery, in the STT, and within the thalamus.4 (Figure 1)

In the brain, there are common structures to the itch pathway and then distinct structures, depending on the type of itch. Within the non-histaminergic pathway, there are separate brain regions, depending on the cause of the itch.3 Pruritogens bind to mostly G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs). Importantly, Mas-related G protein-coupled receptors (Mrgprs) and protease-activated receptors (PARs) on the subset of unmyelinated C fiber somatosensory neurons are itch specific and innervate the skin.3,5,6 MrgprX2 is one of these receptors and is increased in AD and directly correlates with the intensity of pruritus. Recent studies have indicated that while itch is mostly transmitted by C-fibers, some A-fibers were also activated by cowhage (Mucuna pruriens), a plant with hairy pods that cause stinging and itching.7 Experimentally, non-histaminergic itch has been so well replicated with cowhage-provoked itch that they are synonymous.5

Itch-specific neurons are either histaminergic or non-histaminergic.3,6 In this review, the non-histaminergic pathway will be the focus as this is the dominant pathway of itch in AD.5 The chronic itch pathway is initiated when pruritogens bind receptors leading to the opening of the calcium ion channels transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) or transient receptor potential ankyrin 1 (TRPA1) through either the kinase or phospholipase pathway. These calcium ion channels are required for much of the non-histaminergic pathway’s transmission of itch to the spinal cord.8 In the spinal cord, pruritic signals are conducted through the contralateral spinothalamic tract by gastrin-releasing peptide receptors (GRPR)+ neurons.

Itch-Scratch Cycle

The initiation of AD is postulated to be an increased itch sensitivity from central and peripheral sensitization. Thus, pruritus and scratching are provoked by internal or external stimuli that would normally not cause itching. This scratching further disrupts the epidermal barrier and the integrity of the skin, which allows external substances into the skin. This leads to an increased Th2 response and increased Th2 cytokines, such as IL-4, IL-13, and IL-31. These cytokines further lower the threshold for itch and cause more scratching, perpetuating the itch and scratch cycle.7 IL-4 in particular has been implicated in the sensitization of pruritogenic neurons to IL-31, which is one of the most important pruritogenic cytokines.9

Central Sensitization of Itch

It is well known that central sensitization increases pain sensitivity and the maintenance of pain in cases of chronic pain, and recent studies suggest a central sensitization for itch analogous to the central sensitization of pain in chronic pruritus. This indicates a neurologic contribution to pruritus in chronic conditions, such as AD, that can prolong the symptoms of itch and contribute to a decrease in quality of life for these patients.10 The central sensitization of AD can be from less inhibitory signals in the CNS, such as a downregulation of inhibitory GABAergic interneurons. Astrocytes and interneurons in the spinal cord also contribute to central sensitization.

In addition, dorsal spinal neurons express the neurokinin 1 receptor (NK1R), which is the main receptor Substance P (SP) acts through. NK1R and GRPR have important contributions to central sensitization: GRPR has been linked to hyperknesis (overreaction to pruritic stimuli) and NK1R has been linked to both alloknesis (CNS couples non-pruritic stimuli to pruritic pathways) and hyperknesis.8,11 This increased sensitization can be seen through experiments which have shown that in lesional skin in AD the electric stimulation required for itch is less than in healthy participants.

A recent experiment has demonstrated a lower threshold for both mechanically and cowhage-induced itch in lesional skin of AD patients.8 This indicates that AD sensitizes not only the non-histaminergic chronic pathway but also a mechanosensitive pathway that is not normally involved in the transmission of pruritic signals. Inflammation also contributes to sensitization through the activation of spinal cord glial cells by the release of inflammatory mediators from the peripheral sensitization. This sensitization leads to persistent alloknesis and hyperknesis even after inflammation diminishes, which is what causes the severe itching even in relatively mild AD.8

Peripheral Sensitization of Itch

The peripheral sensitization in AD is a decreased activation threshold of pruritogenic neurons that results from inflammation. This increases the nerve fiber responsiveness to pruritogenic signals and increases the neurotransmitters released from these neurons.8 Nerve growth factor (NGF) and IL-31 are both increased in AD, and both increase the branching and sprouting of peripheral sensory nerves.8,12 This hyperinnervation of the skin has been linked to peripheral sensitization and an increase in itch.

Sensory cutaneous afferent nerves transmit pain and itch from the skin to the CNS. NGF upregulates TRPV1 expression on peripheral sensory neurons, which has been linked to lower threshold of activation for those neurons and also has been linked to peripheral sensitization.8 In the dermis and epidermis cells in skin with AD, NGF-reactive cells are significantly increased. The upregulation of NGF promotes the growth and survival of peripheral sensory neurons and sympathetic neurons. NGF increases nerve elongation, sprouting, and survival; all of which sensitizes peripheral cutaneous itch sensory neurons.2,5

The vasodilators Calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) and Substance P are released together from nociceptive C-fibers and have important roles in the development of pain.13 TRPV1 activation, which is increased by NGF, has been found to increase SP and CGRP.8,9 There is an increase of SP and NGF found in the plasma of AD patients, and the CGRP levels were higher in AD patients with severe pruritus.2,14 The level of both NGF and SP have been positively correlated to disease severity of AD. The link between pruritus and SP has been clearly established with intradermal injections of SP provoking itch.2 The upregulation of SP and CGRP from nerves contributes to inflammation as well as hyperknesis.8 Scratching can increase the release of SP and further perpetuate the itch scratch cycle and neurogenic inflammation. Substance P’s direct communication with mast cells contributes to pruritic sensitization by increasing neurogenic inflammation.7,8

IL-31, thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), and TRPA1 are all increased in AD. TSLP elevations can be detected prior to any observable symptoms of AD and can be used for early detection and treatment of the disease. TSLP is released from keratinocytes, and it propagates the cycle of allergic inflammation by producing proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-4 and IL-13, which in a positive feedback cycle, increases TSLP.8,12,15 Both IL-31 and TSLP activate the TRPV1+ TRPA1+ pruritoceptive neurons and therefore directly increase itch.8

SP may also induce itch through TRPA1 neurons because mice without TRPA1 have attenuated SP-induced scratching.15 For IL-31 to induce itch, TRPV1+ TRPA1+ must both be activated.3 IL-31, like NGF, increases the branching and sprouting of peripheral sensory nerves. This is thought to contribute to the increased distribution, thickness, and density of peripheral nerves in AD and to the alloknesis and hyperknesis that is found in the disease, which continues the itch scratch cycle.2,12,16

Morphological Changes of Neurons in AD

Skin is one of the most densely innervated organs. Patients with AD have an even denser nerve innervation in the epidermis compared to healthy controls.17 Increased inflammatory cytokine release and pruritus in AD have been linked to this hyperinnervation.17,18 The nerves that innervate the skin have various morphologies, protein expressions, and sensory functions. For example, pruritogenic C-fibers are unmyelinated and express the neuropeptides, CGRP and SP, which are both increased in AD and implicated in the hyperknesis.8,17 Free nerve endings of the C-fibers are close to the skin cells, dermal fibroblasts, and keratinocytes, and these release factors, such as Semaphorin 3A (Sema3A) and NGF, which affect the surrounding sensory C-fiber’s morphology. These factors can also lead to both growth or pruning of neurons and change the expression of neuropeptides, like CGRP and SP, that can lead to mast cell degranulation, which further sensitizes the pruritogenic nerves. Roggenkamp et al revealed the importance of atypical keratinocytes in changing the morphology and quantity of nerves in the skin of patients with AD.17 This study again confirmed the increase in NGF in AD. It demonstrated the hyperinnervation from NGF led to increased length of CGRP-Immunoreactive nerves, and the chronic increased NGF increased SP and CGRP expression in sensory neurons in the epidermis and papillary dermis. The neurites were unbranched and straight, and were due to the atypical keratinocytes having increased NGF. This study also provides evidence that the morphology and the quantity of peptidergic C-fiber sensory nerves is skin layer specific. This study provides evidence that the morphology and the quantity of peptidergic C-fiber sensory nerves is skin layer specific. In mice models, CGRP peptidergic nerves were straight and the axons terminated in the stratum spinosum. Non-peptidergic fibers grew through the stratum spinosum and branched in the stratum granulosum. The neurotrophic factors (such as NGF) appear to have different effects, depending on the layer of skin. The increased NGF in the epidermis of AD appears to increase itch while an increase in NGF in the epidermis and dermis appear to increase pain.17

IL-31 is another neurotrophic factor that is increased in AD and has been linked to changes in nerve morphology. A mouse study revealed that IL-31 was found to increase nerve branching in dorsal root ganglia neurons and increased length only in neurons with a small diameter. Only these small diameter neurons (<20 μm) had the IL-31 receptor. IL-31, like other neurotrophins, seems to have an important role in actin polymerization and path-finding of the growth cone.19 Pruritogenic neurons have a small diameter, thus the results of this study are consistent with the link between increased IL-31 in AD and itch.

IL-31 and another neurotrophin, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), are increased when eosinophils are activated. Eosinophils can be activated by SP and neurotrophic factors, like BDNF, and all three of these (SP, BDNF, and eosinophils) are increased in AD. It has been shown that eosinophil culture supernatant (even without NGF) increases dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neuronal branching. Many of the increased eosinophils in AD are spatially close to the nerves in the skin. When these eosinophils are stimulated (with platelet-activating factor), there is an increase in BDNF, and there are morphological changes of the DRG neurons not seen in the control. This includes increased growth and branching of skin nerves. Guseva et al attributed most of the morphological changes to BDNF but did concede that other factors like IL-31, major basic protein, or eosinophil peroxidase may contribute.20

Neurotrophic factors (including NGF, BDNF, IL-31), nearby cells (such as eosinophils and atypical keratinocytes), and neuropeptides (like SP and CGRP) are important mediators of neuronal morphological changes in AD, and treatment of these factors and cells should be investigated further.

Shift in Traditional Paradigm

Recent experiments have suggested that the neural changes, such as increased density of cutaneous nerve fibers, are a provoking factor and not just a consequence of atopic dermatitis.2,21 The traditional view has been that these neural changes (and many other unregulated cytokines and factors that have been found in AD) were a consequence of the inflammatory response and subsequent scratching.

However, an experiment in a mouse model of AD showed that the increase in nerve density preceded the inflammation and scratching, and when the neural recruitment was prevented, the inflammation and scratching was also prevented.2,21 A different experiment in a mouse model also challenges the traditional view that hyperinnervation in AD causes pruritus. This study demonstrated that even when treatment inhibited nerve growth, branching, and skin inflammation even more potently than established anti-pruritic treatment, there was no decrease in itch.22 Thus, demonstrating that pruritus and scratching do not always correlate with cutaneous nerve hyperinnervation or with inflammatory infiltration.22 Roggenkamp et al revealed that cultured keratinocytes from AD skin had increased NGF when unstimulated in vitro.17 This counters the previous model that NGF increased from scratching and from inflammatory stimulation.17 This also underscores the importance of early treatment of the neural disturbances in chronic atopic dermatitis. These experiments suggest that if the neural changes in AD can be prevented or treated early, then both inflammation and pruritus could be controlled.

Acute and Chronic Changes in AD

AD is a chronic relapsing disease, so patients can have acute and chronic lesions simultaneously during exacerbations of the disease.23,24 Through RNA sequencing of acute and chronic lesions, it has been shown that much of the cytokines and immune responses that are increased in acute lesions are also increased in chronic but are found to a larger extent in chronic.24

In acute AD, the increase in IL-4 and IL-13 leads to sensitization of pruritogenic neurons (likely NP2 and NP3). IL-4 and IL-13 also increase nerve elongation leading to hyperinnervation. The increase in IL-31 in acute AD directly induces itch and/or leads to pruritogenic sensitization. IL-31 levels have been found to directly correlate with severity of itch symptoms in AD.16 IL-22 increase leads to acanthosis (a thickening of the stratum spinosum), which is further increased in chronic AD.7

Scratching leads to SP release from peripheral nerves and increases the NGF, IL-31, histamine, and tryptase released from the nerves. These all cause increased neurogenic inflammation and induce further itching and scratching. In chronic AD, the itch scratch cycle leads to more external pruritogenic stimuli entering the epidermal barrier causing more inflammation, which further disrupts the barrier creating a vicious cycle.7 The increase in cytokines, inflammatory mediators, and the sensitization of the peripheral pruritogenic nerves that are seen in chronic AD is likely due to this positive feedback loop through the itch-scratch cycle. The difference between acute and chronic AD appears to be the higher amount of the increased cytokine expressed in chronic rather than different cytokines being expressed.24

Psychological Stress and AD

CNS and skin express many of the same receptors for neurotransmitters and neuromodulators, and when these are dysregulated, as in periods of chronic stress, these mediators can contribute to the pathogenesis of AD. Stress leads to an increase of neuropeptides and neurohormones in the brain and peripheral nervous systems, which have been implicated in pruritus and in AD. These neuromodulators from stress, such as SP, can cause hyperinnervation of skin, further increasing the alloknesis and hyperknesis in AD.2,8 Serotonin in normal skin is relatively non-pruritogenic, however, in AD it has been found to strongly provoke itch.16

The link between psychological stress and flares of AD and pruritus has been well-established with 81% of patients with AD reporting that stress worsens itch symptoms. Stress has been found to disrupt the epidermal barrier through the upregulation of glucocorticoids. In healthy participants, glucocorticoids decreased stratum corneum integrity. Short term use of glucocorticoids decreases the integrity and cohesiveness of the stratum corneum. Glucocorticoids are released from the adrenal gland during times of stress, which is likely the reason that in an experiment of tape stripping, there was an increased rate of epidermal barrier disruption in students who were under stress from examinations. This disruption was decreased when the students were not stressed.2 This indicates that stress can further increase skin barrier dysfunction and risk of skin infections, especially in disease states like AD where there is epidermal disruption, as either the initial trigger or as a consequence of the disease.2,25

Sympathetic nerves release neuropeptide Y (NPY), an adrenergic agonist. In the epidermis of AD lesioned skin, there are significantly more NPY-positive cells than in healthy controls. In addition, in AD patients with higher state-trait anxiety scores, there were more NPY and NGF cells than AD patients with lower anxiety. This increase in sympathetic response in AD patients is also supported through the consistently higher heart rate measured in AD patients even without stress.2

Selected Treatments Targeting the Neurobiological Changes in AD

Topical corticosteroids are the first line of therapy for treating AD and for managing chronic itch in AD. Corticosteroids efficacy in treating the inflammation from AD is well-established and has been used for over 50 years. It has been demonstrated through numerous studies that corticosteroids also decrease itch. There are many corticosteroids that all have different specific mechanisms of action and potencies. In an AD mouse model, topical prednisolone decreased itching and NGF in skin.26 This decrease in NGF would lead to a decrease in the hyperinnervation in AD and reveals a possible neuronal mechanism of action for corticosteroids. Corticosteroids were found to decrease itch from all the pruritogens tested in this study: histamine, SP, serotonin, and PAR-2 agonist. This study did not demonstrate a morphological change in neurons, thus indicating the attenuation in itch was due to functional changes in the pruritogenic neurons. This study hypothesized that the decrease itch due to histamine and serotonin could be due to a decrease in phospholipase C Beta 3 which is part of the pathway for itch on C fibers that are TRPV1+. There also appeared to be a TRPV1 independent pathway because serotonin, histamine, SP, and PAR-2 agonist provoked itch decreased even after TRPV1 neurons were depleted. This study did not discover the TRPV1+ independent pathway, but in the future, this should be further researched to elucidate the mechanism of action of corticosteroids.27 Topical corticosteroids tend to only be used for short to medium treatment because of side effects and tachyphylaxis, reduced treatment efficacy at the same dose. This tachyphylaxis and long-term use leads to higher use of the steroids for the same response and increases the risk of side effects, such as skin thinning, atrophy, folliculitis, impetigo, and adrenal suppression.16

Other topical treatments have also been found to decrease chronic itch. Topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCIs), such as tacrolimus and pimecrolimus, are second line for AD. They are used on more sensitive areas, such as the face and as prophylaxis. Their main mechanism of action is decreasing inflammatory cytokines. TCIs have been shown to significantly decrease itch as well as inflammation. It is thought that this anti-pruritic mechanism of action is through the overstimulation of TRPV1 that leads to the desensitization of pruritogenic nerves.28 TCIs as well as Anti-NGF and Sem3A (which is antagonistic to NGF) have also been found to treat itching in AD through the normalization of the hyperinnervation in AD and treat itching.22,29 Topical anesthetics, such as lidocaine and prilocaine, have been used to decrease itch by stabilizing the sensory neurons by targeting the transient receptor ion channel family and preventing itch transmission.16,28 Topical capsaicin has been found to reduce itch, but it was recently discovered that it can also increase chronic itch. It has been postulated that this increase in itch may be due to the increase in TRPV1 neurons seen in AD.16

Phototherapy has also been shown to control itch in AD. The mechanisms of action that attenuate itch in phototherapy are not completely elucidated. Studies have suggested that phototherapy works to decrease itch by decreasing inflammation and changing neural pathways. Ultraviolet A 1 (UVA1) and narrowband UVB (NBUVB) are the preferred modality of phototherapy for AD, although other wavelengths are efficacious. UVA1 has been found to decrease IL-4 and IL-13. Low doses of UVA1 and NBUVB decrease IL-31.30 IL-4, IL-13, and IL-31 have all been implicated in the itch-scratch cycle and found to increase hyperinnervation of the skin and cause sensitization of pruritogenic neurons.12,16,30 Thus, treatments decreasing these cytokines interrupt the itch-scratch cycle and the central and peripheral sensitization implicated in AD. NBUVB and UVA have been found to decrease CGRP positive nerve fibers.30 Increase in CGRP has been linked to inflammation and hyperknesis, thus a decrease in these nerves can treat the pruritus and inflammation that decrease the quality of life of these patients.8,30 NBUVB is usually used for the management of chronic disease and UVA1 for acute flare-ups. UVA with psoralen (PUVA) is also used and comparable to the efficacy of NBUVB.30

Phototherapy may also decrease itch through the opioid system. PUVA has been found to decrease mu-opioid receptors and does not affect kappa-opioid receptors.30 Kappa opioid receptor agonists and/or mu-opioid receptor antagonists can decrease itch. Specifically naltrexone, a competitive opioid antagonist, and butorphanol, a kappa agonist and a mu antagonist, have been found to significantly decrease pruritus.28

Additional treatments being studied or utilized to treat itch in AD are found in Table 1.

Discussion: Clinical Implications

Chronic lesions show more changes in genes, immune response, morphology, and neuroanatomy. As more time goes on, there is a perpetuation and amplification of the itch/scratch cycle, leading to increased sensitization of itch, hyperinnervation of cutaneous afferent nerves, and of hyperknesis and alloknesis that can persist even after the inflammation has been treated and resolved. This indicates that some of the neurologic changes in the skin of AD are irreversible or persistent after treatment. This underscores the importance of early treatment, especially in treatment that targets the neurological changes of AD. This is not currently emphasized in guideline documents but appears to be justified by the chronicity of hyperknesis and alloknesis even after other aspects of the disease are treated. Hyperknesis and alloknesis are not life threatening but significantly contribute to the disease burden and diminish the quality of life in those with AD. Treatments should continue to focus on alleviating these symptoms.

The hyperinnervation of cutaneous afferent nerves that is characteristic of AD should also be treated and treated early in the disease before the itch/scratch cycle further amplifies the inflammation and the hyperinnervation. Not all treatments that decrease nerve growth in AD decrease pruritus. It has been postulated even after the nerve density is normalized there is peripheral and central sensitization that can maintain itch. There are many treatments that decrease this hyperinnervation and decrease itch. These treatments, such as anti-NGF, Sem3A, and tacrolimus, achieve both effects and can be used in refractive pruritus in AD or to prevent incessant alloknesis or hyperknesis.

The treatment and prevention of the neuronal symptoms offers a new avenue to treat AD, especially chronic treatment resistant pruritus.

Conclusion

Atopic dermatitis is primarily regarded as an inflammatory disease, however new studies are revealing neuronal changes may occur earlier in the disease process and are larger contributors to the etiology of the disease than what the traditional paradigm has suggested. In recent years, there has been an emphasis on research of the mechanism of action of these neuronal changes, such as hyperinnervation and sensitization. These mechanisms and the numerous cytokines and receptors that have been implicated in these neuronal changes are the target of many new treatments and medications. Advancements in AD research hold promise for properly diagnosing and treating a condition that can impair bodily processes, cause substantial discomfort, and lead to secondary infections. Treatments targeting neuronal changes in the disease are an exciting field of discovery.

Disclosures

Dr. Lio reports being on the speaker’s bureau for AbbVie, Arcutis, Eli Lilly, Galderma, Hyphens Pharma, Incyte, La Roche-Posay/L’Oréal, Pfizer, Pierre-Fabre Dermatologie, Regeneron/Sanofi Genzyme, Verrica; reports consulting/advisory boards for Alphyn Biologics (stock options), AbbVie, Almirall, Amyris, Arcutis, ASLAN, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Burt’s Bees, Castle Biosciences, Codex Labs (stock options), Concerto Biosci (stock options), Dermavant, Eli Lilly, Galderma, Janssen, LEO Pharma, Lipidor, L’Oréal, Merck, Micreos, MyOR Diagnostics, Regeneron/Sanofi Genzyme, Sibel Health, Skinfix, Suneco Technologies (stock options), Theraplex, UCB, Unilever, Verdant Scientific (stock options), Verrica, Yobee Care (stock options). In addition, Dr. Lio has a patent pending for a Theraplex product with royalties paid and is a Board member and Scientific Advisory Committee Member emeritus of the National Eczema Association.

Mary McCarthy has no conflicts of interest or relationships to disclose.

Funding

This research received no funding.